We recommend

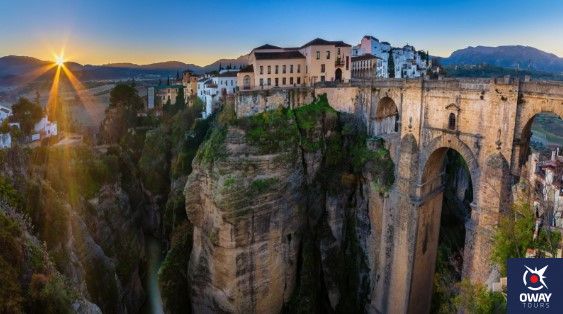

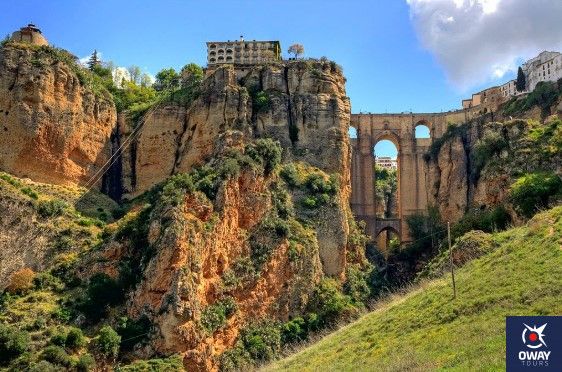

The Puente Nuevo (New Bridge) is the most emblematic and beautiful monument in the city of Ronda, built between 1751 and 1793. It spans the Tajo de Ronda, a gorge more than 100 metres deep, which was carved out by the Guadalevín River over time. If you want to visit the city of Ronda and delight in the beauty of this romantic landscape, stay and read this article to learn more about the Puente Nuevo de Ronda before you visit.

The Puente Nuevo Bridge in Ronda is a universal symbol of one of the most visited cities in Andalusia, Malaga. It is an engineering marvel that took a great deal of effort to build and, in turn, allowed the municipality to expand naturally, split in two by the Tajo River. This construction allowed the population to grow towards the Mercadillo pasture, now known as Plaza de España.

The design of the bridge dates back to 1542, but it was not until 1735 that construction of the first bridge began. A structure 100 metres high and 35 metres in diameter was built in a single arch. However, poor execution of the project, poor closure of the arch and lack of supports contributed to the structure collapsing six years after its construction. Fifty people died in the collapse, and hundreds of tonnes of stone ended up at the bottom of the ravine. This terrible accident led to the design of the current bridge that we all know today. The construction of a bridge of this magnitude in the first half of the 18th century was a real milestone in the history of bridges, surpassing all other structures of this type that had been built on the planet, except for those built by the ancient Roman Empire.

However, despite this tragic event, today we can enjoy the architectural and monumental jewel that is the Arch of Philip V. In order to allow traffic to flow, the section of wall that was blocking it was removed and a ramp and the aforementioned Arch were built in an attempt to improve access to the city, but the steep slope was not ideal, especially given the added difficulty for carriages to pass.

As explained by historian Faustino Peralta and confirmed by documents preserved in the Virtual Library of the Serranía de Ronda thanks to research by Aurora Melgar, work on the Puente Nuevo resumed in 1759. In a study carried out by Rosario Camacho and Aurora Miró, entitled ‘Antecedentes del Puente Nuevo de Ronda’ (Background to the New Bridge of Ronda), we can see the different projects that were considered for the construction of the bridge.

Financing posed some problems, with financial contributions coming from different towns: 15,000 reales from the Real Maestranza and even transactions carried out at the May Fair. The plans were drawn up by José Martín de Aldehuela, who oversaw the construction of the main arch and the upper road. On 4 November 1787, the bridge was opened to traffic and today is crossed by hundreds and hundreds of visitors to this iconic structure. The bridge was finally inaugurated in May 1793.

It is made of stone masonry, featuring a central semicircular arch that rests on a smaller one, under which the river flows. At the top are the bridge’s rooms that served as a prison, and on either side are two other semicircular arches that support the part of the structure that holds up the street.

Ronda’s location is somewhat unusual, as it is nestled between mountains. For its residents, tourists and visitors alike, this isolated setting surrounded by nature and vegetation is incredibly beautiful. If you are travelling in your own vehicle from Málaga, simply take the A-357 towards Ronda. By bus, Ronda is connected to the main cities in the province, such as Málaga and Marbella. It is also connected to other Andalusian provinces, such as Cádiz and Seville. You can also travel by train, especially from Málaga, Antequera, Algeciras and Madrid.

The best views of the Puente Nuevo bridge can be found at the end of a small path that runs from the Plaza de María Auxiliadora. The desire to build a bridge that would safeguard the cliff crossing the Tagus always existed, first among the Arabs and later among the Christians. After the Christian conquest in 1485, life in the town developed rapidly, and the large increase in population demanded the construction of a new bridge. The attempt to build the bridge in the 16th century was unsuccessful, as the technical difficulty involved was enormous. Finally, its construction between 1759 and 1793, over more than three decades, was a feat of great skill and is considered a masterpiece of engineering. Despite its enormous size, the bridge blends in perfectly with the natural rock, as its colour blends in with the cliff walls. This is because the material used was extracted from the bottom of the river gorge after the first collapse.

José Martín de Aldehuela, the enigmatic architect of the bridge, is also credited with the construction of the Ronda bullring, although this has not been confirmed. He arrived in Málaga at the request of Bishop Molina Larios to build the foundations of Málaga Cathedral, as the architect had previously worked with great skill on Cuenca Cathedral. However, there are many legends surrounding this bridge, one of which says that Martín de Aldehuela committed suicide on the Puente Nuevo because he could not conceive of a better bridge than this one. His remains are buried under the square of the convent of San Pedro de Alcántara in Malaga.

Above the main arch of the Puente Nuevo there is a small window which, as we mentioned earlier, is a hidden room that served as a prison and later became an inn, transforming what was considered a punishment into a privilege. Today, it is an interpretation centre for the environment and history of the city, where different photographs and videos are displayed that tell the story of the Puente Nuevo. On some days, when the wind blows fiercely under the arches of the bridge, loud whistling sounds are produced and the wind lifts the water from the river, which is why it is often said colloquially that ‘it rains upwards’.